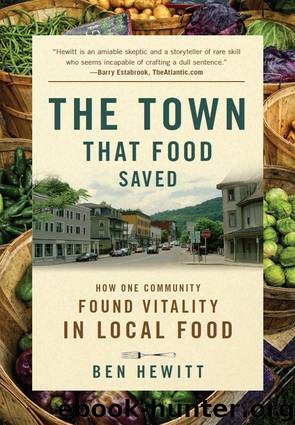

The Town That Food Saved by Ben Hewitt

Author:Ben Hewitt

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale

Published: 2010-06-05T04:00:00+00:00

* * *

Tom Gilbert trades in a very different model of soil fertility. That much was clear the moment we arrived at the composting site, which sits at the edge of a broad expanse of ridgetop farm field on Hardwick’s West Hill Road. The entire operation covers less than an acre; there were a small, shacklike office, a bucket tractor for flipping compost piles, and a pair of small concrete bunkers where livestock mortalities (or “morts”) are laid and layered with other materials to decompose. Under ideal conditions, it takes less than three weeks for bacteria to consume the flesh of a 1,500-pound dairy cow. There were also a dozen or so piles of compost and compost feedstocks in varying degrees of decomposition. It was a cool day, but the air still smelled strongly of something rotting. It wasn’t a bad smell, per se, but I didn’t spend much time breathing through my nose, either, and I chose to believe that the odor was not of animal origin.

Highfields is a fairly new enterprise; it was founded in 1999 by Tod Delaricheliere, a local dairy farmer who’d spent the previous four years experimenting with composting the manure excreted by his cows. There are numerous reasons to compost manure, rather than applying it fresh. For one, the composting process literally cooks the pathogens (E. coli, Salmonella) that could catch a ride on, say, a head of lettuce and cause a potentially fatal illness. That’s why vegetable farmers never spread fresh manure. But even in circumstances where fresh manure can be applied (many farmers still spread it on their hayfields, for instance), composting is preferable. That’s because nitrogen—the critical nutrient in crap—is extremely volatile. It doesn’t want to just lie there on your field, seeping contentedly into the ground and nourishing the roots below the surface; it would far rather return to the atmosphere as a gas. Fresh manure can lose as much as half of its nitrogen content within 12 hours of being spread.

As Gilbert explains it, the act of composting is really nothing more than creating a nitrogen bank. Bacteria and fungi develop, consuming nitrogen and storing it in their microscopic bodies as protein. When one dies, it is cannibalized by its peers. With proper management, it takes less than a month to convert a pile of unstable nitrogen and carbon into a finished pile of biomass. Spread on a field, compost will release its nutrients over a period of years, rather than hours and days. “Think of it as a time-release vitamin for your soil,” said Gilbert.

Gilbert began working at Highfields in 2000; a native of Brooklyn, he’d begun to distance himself from his urban upbringing at an early age, courtesy of an uncle who cultivated corn, soy, and wheat in rural Kansas. When Gilbert was 14, he spent a summer on his uncle’s farm, and those months under the relentless sun of the US breadbasket affected him profoundly. “It excited me so much to be part of such a

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5520)

The Sports Rules Book by Human Kinetics(4349)

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff(4255)

ACT Math For Dummies by Zegarelli Mark(4029)

Unlabel: Selling You Without Selling Out by Marc Ecko(3630)

Blood, Sweat, and Pixels by Jason Schreier(3586)

Hidden Persuasion: 33 psychological influence techniques in advertising by Marc Andrews & Matthijs van Leeuwen & Rick van Baaren(3525)

Bad Pharma by Ben Goldacre(3400)

The Pixar Touch by David A. Price(3395)

Urban Outlaw by Magnus Walker(3369)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(3195)

Kitchen confidential by Anthony Bourdain(3055)

Brotopia by Emily Chang(3033)

Slugfest by Reed Tucker(2979)

The Content Trap by Bharat Anand(2892)

The Airbnb Story by Leigh Gallagher(2825)

Coffee for One by KJ Fallon(2603)

Smuggler's Cove: Exotic Cocktails, Rum, and the Cult of Tiki by Martin Cate & Rebecca Cate(2502)

Beer is proof God loves us by Charles W. Bamforth(2423)